How can we move beyond this conversation stopper?

Urban infrastructure can kickstart farming careers!

BoerenBruxselPaysans is a pilot project in the peri-urban fringe of Brussels seeking to offer new farmers the needed impulse to provide Brussels with local, healthy, qualitative and affordable food. Through the coalition of existing grassroots movements with government aid under the coordination of the Brussels regional authority and European funding, the project was able to set up a broad range of supportive infrastructure for starting farmers. The municipality of Anderlecht offers land as an espace-test or farmstart for farmers that want to test out their business model. The grassroots movement Début des Haricots offers practical training courses and links the test-farmers with their spin-off network GASAP—different consumer groups in the city of Brussels that are running a vegetable box-scheme. Maison Verte et Bleue runs a community kitchen and will help the local farmers to operate the future conserverie and packaging facility and Terre-en-vue, an access to land organisation, scouts more permanent and lasting land use agreements across the city for when farmers went through the testing period. The municipality of Anderlecht chose not to sell off residual agricultural infrastructure that marked the neighbourhood, but rather invest in the renovation and programming of these farm buildings to support growers and food initiatives in this part of the city. By focusing on infrastructure, BoerenBruxselPaysans creates literally the supporting environment that enables a constant inflow of new and transitioning farmers. It also creates a node in a wider landscape, holding the potential to offer their supporting infrastructure to many more farms in the area. Could we imagine the migration of the farm start to other locations, rather than moving the farmers that have invested in the soil and have in the meantime become networked within a local community?

Taking root in neighbourhoods

Rosario’s municipal Urban Agriculture Programme is founded on the concept of the ‘huerta’- a garden park where residents can be assigned a plot of land so that they can grow vegetables for consumption and for sale. The huerta provides a focal point for the development of ‘productive neighbourhoods’, in which agriculture is integrated in social economy programmes focused on construction and maintenance. The huertas also provide nutrition, education and employment for residents, who can sell directly or through markets and specialist retail outlets which are also supported by the Urban Agriculture Programme. They are also spaces open to the community who can enjoy the garden parks, purchase the locally produced crops and find out more about food growing in general. These public gardens - located on both public and derelict private land - form part of a decentralized model of municipal management and aim to provide both a growing space and a market within each neighbourhood. The 2 hectares Parque Huerta Oeste, inaugurated in 2020, is the most recent of 7 garden parks in the city.

Sharing among family members, friends, neighbours and colleagues

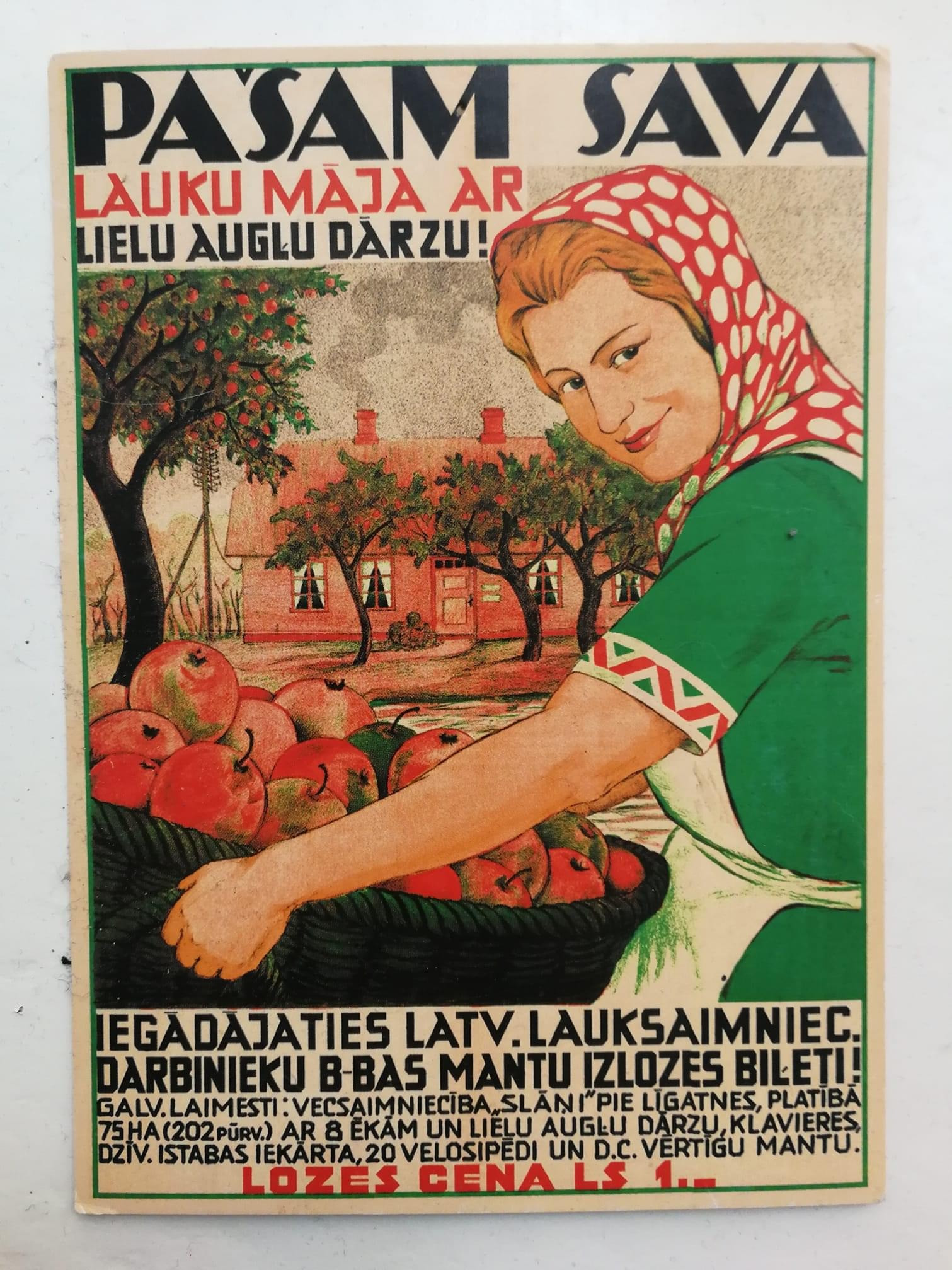

In amateur gardening and livestock farming, an occasional or seasonal overabundance of produce is inevitable. In the Latvian context, not unlike other post-socialist states, the free sharing of surplus is still a common practice and rooted in a long history of auto-production. Sharing is not limited to family members, but includes a wider network of colleagues, friends, and neighbours. This tradition partly stems out of a sense of solidarity and dates back to times of Soviet occupation when food and other resources were scarce, and family members of different generations had to actively support each other. While today, sharing is no longer a bare necessity, interviews carried out as part of the Urbanising in Place project show that people find joy in offering others self-grown food, and feel pride for their own accomplishment. And even those in need do not hesitate sharing the surplus of their self-grown produce.

These practices are often not considered within sustainable food planning initiatives. Individuals and communities involved in informal practices of food sharing are not campaigning around such practices. Local farmers engaged in direct selling initiatives tend to replace informal traditions of sharing. Can we imagine urban food policies in which self-growing and sharing practices would be celebrated and valorized?

Material Feminists against patriarchy

The current dominant approach to food is based on individual choices: people choose what to buy and most worryingly, how much food to waste individually, or as part of their family arrangements. The current food system approach does little to include considerations of what food is available, how this relates to a colonial past, and how this is prepared and eaten. Often women are expected to be in charge of food preparation even when they have caring responsibilities and a full time job outside the home. However, the emerging community kitchen movement can build on the historical imaginary of the materialist feminist movement of the late Nineteenth century, which has been envisioning a world in which kitchens where part of social collective arrangements, rather than individualised segregated spaces aligned with patriarchal oppressive family structures.

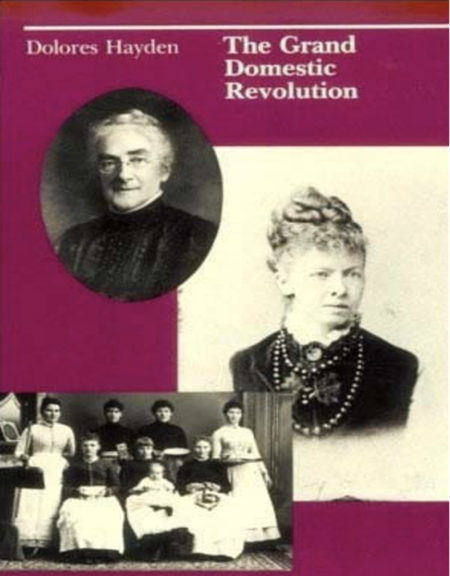

“The Grand Domestic Revolution” - book cover

A multiplicity of spatial and social arrangements were experimented and designed: from kitchenless houses with shared housekeeping facilities, to large scale co-housing /neighbourhoods with central kitchens (see image). Contemporary, agroecology-based and politically-active community kitchens can help to reconsider food and meal production as a collective responsibility, challenging patriarchy and colonialism both in the fields and in the house.

© Hayden, as cited in DICK URBAN VESTBRO and LIISA HORELLI (2012), “Design for Gender Equality: The History of Co-Housing Ideas and Realities” in Built Environment, Vol. 38, No. 3, Co-Housing in the Making (2012), pp. 315-335