The Territorial Food Hub is an organisation that is a central component (or node) of a wider agroecological food system or network that operates within, and is closely identified with, a specific neighbourhood or district. It provides some degree of coordination, nurturing and shared identity to the different food businesses operating within the local system. It acts to connect them to each other and to other local place-based initiatives and infrastructure and to the local municipality. In addition to providing practical support and access to assets and resources, the Territorial Food Hub can have a critical role in helping local communities (that have long been used to not having sense of ownership of anything in their neighbourhood) to develop such a stake in their living places, enter in dialogue, overcome colonial attitudes to food, and build food democracy.

Why a Territorial Food Hub?

Inspiring practices for the Territorial Food Hub take a variety of different forms and have arisen in response to a range of different needs, opportunities and organisational, social and economic dynamics.

Placemaking and place based solidarities

Urban planning and regeneration activities are increasingly framed in terms of ‘placemaking’. This is a term which can be used both to describe a process which engages residents in a participatory process of planning and development, and as an objective; the creation of a place with a strong sense of character and identity, which draws on its history and heritage, to which people connected, and which includes high quality spaces to live, work and play. The investment in attractive environments, to live and work directly contributes to the liveability for all involved. Place lies at the basis of a way of working that is not structured around specific groups but starts from proximity and the co-presence of groups in a given site, street or neighbourhood. Place holds the potential to build social interaction at the intersection of various aspirations, capabilities and (group) identities, and to structure a politics of place that shape solidarities within this intersection (Harcourt and Escobar 2002). Local food cultures can play a significant role in the creation of a sense of place and local identity whilst territorial food hubs that support their development may bring underutilised or derelict land and buildings - both public and private - back into productive use.

In 2017 a consortium of community organisations took on management of the 2.5 acre Wolves Lane Centre, a council owned ex plant nursery site containing a number of large glasshouses in Haringey, North London. The vision for the site is to develop a thriving community food project with opportunities for collaboration with and involvement of Haringey residents in education, enterprise and health and wellbeing activities. This is also reflected in the consortium of actors behind the management – or better, stewardship – and process of renovation for the site, ranging from community-based actors (Ubele Initiative), organic growing and training (OrganicLea) and local food distribution organisations (Crop Drop) to land advocates (Shared Assets) The consultative design process lead to a development plan for the Wolve’s Lane Centre (see also here) that includes public events/community building connecting people with the outdoor and indoor growing spaces, allowing reallocation of glasshouses currently used for this purpose and fit-for-purpose new facilities for community learning, community hires and operational activities.

Wolve’s Lane is inspiring in light of the search for an agroecological urbanism, as it reveals how residual urban infrastructure – in this case, a former municipal plant nursery – is re-interpreted as a community-driven space where agroecological principles permeate a series of local initiatives and construct a set of solidarities between groups pursuing different social and ecological agendas.

Localism, decentralised systems and social infrastructure

The withdrawal of the state at a national and local level in many countries over several decades has been accompanied by a focus on ‘localism’. This has included a larger role for the community in delivering services previously delivered by the state, and in managing - or in some cases taking ownership of - public land and buildings for community benefit. Territorial food hubs, sometimes operating from or taking ownership of public land and buildings, both deliver and support others to deliver food-based education, training and wellbeing activities.

Atelier Groot Eiland is a social economy organisation committed to giving people a better chance on the labour market and has been active in Molenbeek, Brussels for over 40 years. The non-profit offers work experience, pre-training, employment support and job support. The organisation has grown to become a collection of mini-companies, offering training in a wide range of skills: the Bel Mundo and RestoBEL restaurants, the Bel'O sandwich shop, the Klimop carpentry shop, the Bel Akker urban vegetable gardens and pick-your-own farms, The Food Hub organic shop, the creative workshop and the bakery of ArtiZan, each have their own employees and customers, and thus respond to the needs of different neighbourhoods in Brussels. The organisation is particularly investing in connecting to the surrounding neighbourhood and actively strengthening a local Molenbeek identity – leading to a lovely mix of French and Dutch in their social media. More recently, Atelier Groot-Eiland has started a 1.5 hectare self-picking CSA project in the peri-urban area and is more and more approached by urban actors and local authorities to actively participate in urban redevelopments, acting as a socially driven and sustainable placemaker.

Sustainable production and consumption

As food production has become increasingly globalised and industrialised, local and traditional food growing practices, economies and infrastructure have been lost, leading to the creation of ‘food deserts’ and a rise in interest and concern about the quality, sovereignty and sustainability of our food supplies. This has resulted in the development of place-based initiatives such as Sustainable Food Places in the UK. These partnerships involve local authority and public sector bodies, civil society organisations, businesses and academic institutions who come together to develop a vision, strategy and action plan for not only promoting the production and consumption of healthy and sustainable food, but making it one of the defining characteristics of the place.

Place-based action

Action on the sustainable production and consumption of food is often led by municipalities and other institutions and considers a wide range of action and policy in relation to food and diet. However it has often been accompanied by an increasing interest in food growing both in terms of self growing in allotments or private plots, and in the establishment and growth of non-profit community food growing enterprises, such as cooperatives, CSAs and social enterprises. Where local food growing cultures have taken root there has also often been a flourishing of associated projects and enterprises processing, distributing and selling locally grown food through box schemes, cafes, market stalls and shops, and projects providing training, education and wellbeing services through growing, foraging, cooking and preserving. The Territorial Food Hub can act as a key node in these networks of local food enterprises and projects, often well connected by personal, social and political relationships, shared values and a shared desire to create a new, more local and more socially just food system.

Rosario’s municipal Urban Agriculture Programme is founded on the concept of the ‘huerta’- a garden park where residents can be assigned a plot of land so that they can grow vegetables for consumption and for sale. The huerta provides a focal point for the development of ‘productive neighbourhoods’, in which agriculture is integrated in social economy programmes focused on construction and maintenance. The huertas also provide nutrition, education and employment for residents, who can sell directly or through markets and specialist retail outlets which are also supported by the Urban Agriculture Programme. They are also spaces open to the community who can enjoy the garden parks, purchase the locally produced crops and find out more about food growing in general. These public gardens - located on both public and derelict private land - form part of a decentralized model of municipal management and aim to provide both a growing space and a market within each neighbourhood. The 2 hectares Parque Huerta Oeste, inaugurated in 2020, is the most recent of 7 garden parks in the city.

Resilient local economies

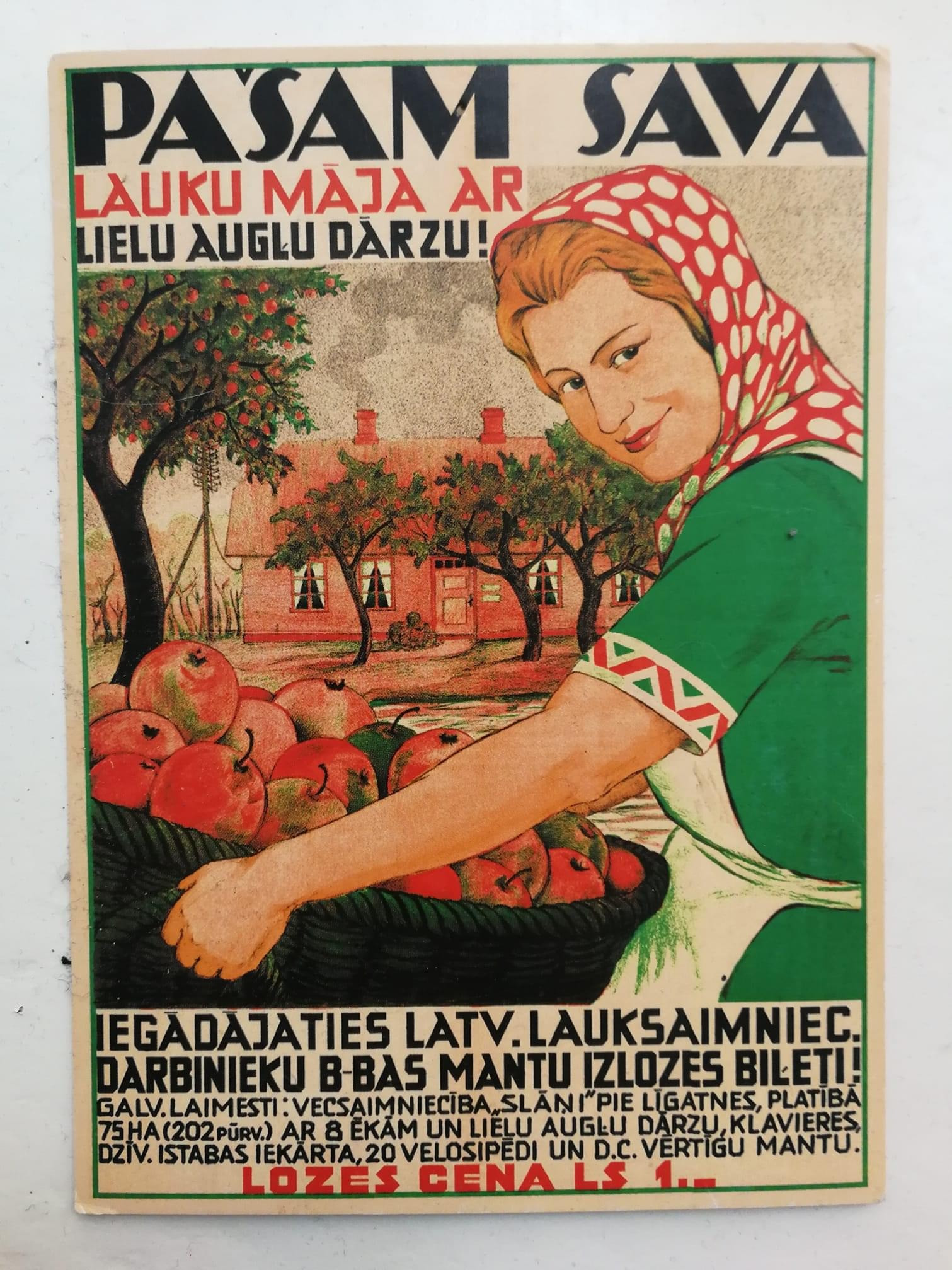

The networks identified above are also often connected by economic relationships or relationships of value exchange, based on the supply of produce and services. As globalisation has accelerated in recent decades there have been increasing concerns raised about the lack of resilience of long global supply chains to disruption. This lack of resilience has been demonstrated by the disruptions caused to the supply of both produce and migrant agricultural labour by the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast local systems of food production, distribution and retail have proved resilient in both during the pandemic and more historical crises. This resilience is based both on their independence from global supply chains, but also in the strength of relationships between producers and consumers which enable a degree of predictability and mutuality in terms of demand, supply, pricing and labour. It is also often based on non-financial forms of value creation and exchange such as the sharing and exchange of food, seeds and labour. Such resilience is exemplified by the local food growing and food sharing cultures in Riga which have been maintained in response to histories of occupation and economic disruption, and in Rosario where the municipal urban food project was established in response to the Argentine economic crisis of 2001.

In amateur gardening and livestock farming, an occasional or seasonal overabundance of produce is inevitable. In the Latvian context, not unlike other post-socialist states, the free sharing of surplus is still a common practice and rooted in a long history of auto-production. Sharing is not limited to family members, but includes a wider network of colleagues, friends, and neighbours. This tradition partly stems out of a sense of solidarity and dates back to times of Soviet occupation when food and other resources were scarce, and family members of different generations had to actively support each other. While today, sharing is no longer a bare necessity, interviews carried out as part of the Urbanising in Place project show that people find joy in offering others self-grown food, and feel pride for their own accomplishment. And even those in need do not hesitate sharing the surplus of their self-grown produce.

These practices are often not considered within sustainable food planning initiatives. Individuals and communities involved in informal practices of food sharing are not campaigning around such practices. Local farmers engaged in direct selling initiatives tend to replace informal traditions of sharing. Can we imagine urban food policies in which self-growing and sharing practices would be celebrated and valorized?

Territorial food hubs have arisen from, and help to embed and develop these dynamics of localism, sustainability, connectedness and resilience. Whilst a business or project in its own right, delivering one element of the local food system, it is also outward looking; proactively nurturing, connecting up, making visible, and supporting the development of sustainable food systems within a specific area or place with which it is itself strongly identified.

Vision & Strategies

The Territorial Food Hub is an organisation that is a central component (or node) of a wider agroecological food network that operates within, and is closely identified with, a specific neighbourhood or district within the city.

Whilst it usually undertakes its own specific core function (such as food growing, training, education, food distribution or retail) it also acts as a ‘hub’ for agroecological activity within the neighbourhood. This wider activity – growing, selling, processing, education, awareness raising, and advocacy – might be undertaken by a range of other organisations and individuals. The Territorial Food Hub is therefore characterised not by its core function but by its social power and its people’s energy that actively makes connections acting as a critical node in a local network. In doing so, it builds local capacity (at district level) to retake control over and manage local resources and to build a new set of economic and social relations.

The Territorial Food hub seeks to act outwardly as well as delivering its own core activity in order to create or nurture with others an alternative food system within their local place. Its activities may include:

nurturing trading relationships between different organisations,

seed sharing and other non commodified sharing relationships such as the sharing of skills, labour, or equipment,

developing a shared sense of identity and power,

coordinating events and activities that include different local food organisations including; talks, festivals, meals, educational activities, and skills and knowledge exchanges,

acting as a link between the wider network of organisations and local or national policy makers and funders,

sharing information, lobbying and awareness raising, and

owning, appropriating or holding assets that can be used by other members of the local network, such as glasshouses, allotment sites equipment, market stalls, kitchens etc

Broadly, the Territorial Food Hub acts to coordinate and promote socially inclusive and multifunctional programming in close cooperation with other local food growing or distributing organisations. As well as providing practical support and access to assets and resources, it can have a critical role in helping local communities (that have long been used to not having sense of ownership of anything in their neighbourhood) to develop such a stake in their living places, enter in dialogue, overcome colonial attitudes to food, and build food democracy.

Learning from existing practices, we see that building transformative Territorial Food Hubs in an urbanised context can be strengthened and accelerated by different factors. Firstly, it is important to start by recognizing the wider value creation that such a hub sets forth, going beyond food production and efficiency. Also the recognition by local municipalities of the value of local food economies to place making and local identity and subsequent inclusion in funding, regeneration and development programmes is an important enabling condition. Local municipalities can play role in the provision of land and assets – such as former glasshouses as is the case for Wolve's Lane, or can co-invest in the development of local community led economic strategies. Thirdly, in the setting up of a Territorial Food Hub, understanding the local economy and social context is key. It is crucial to invest in the work needed for a network to be enabled, to 'see itself' and identify where it is strong, where there are gaps, and to self organise in terms of communication, coordination, in developing governance structures and arrangements etc.

Practice Architecture and Studio Gil worked with a consortium of organisations including Ubele, Crop Drop, Shared Assets and OrganicLea to draw up a masterplan for Wolves Lane Horticultural Centre.

Harcourt, W., Escobar, A. (2002) Women and the Politics of Place. Development 45, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1110308

Marta Soler Montiel (2022) “Le Programme d’Agriculture Urbaine de la ville de Rosario en Argentine,” Revue d’ethnoécologie [En ligne], 8 | 2015, mis en ligne le 31 décembre 2015, consulté le 26 novembre 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnoecologie/2390