How can we move beyond this conversation stopper?

Cooking together is a good start

The network of the Cuisines de Quartier started in Brussels in 2019, originating from several previous action-research projects looking into the accessibility of healthy and organic food. Of course, the price came up as an issue in these trajectories, but also the lack of decent kitchen infrastructure and time for cooking, and cultural and dietary differences were identified as obstacles. As such, the non-profit organisation supports mostly self-organised community groups to frequently cook together and connects them to kitchens, for example the one of a local community centre or school. Although inspired by the Cuisines Collectives in Quebec, the network of Cuisines de Quartier (neighbourhood kitchens) specifically does not only target precarious groups, but strives to be a movement with a big diversity of groups that can learn from each other. Several activities are set in place within the network to link to agroecological initiatives, such as pedagogical activities and games on needs, cultural habits and demands, understanding of additives and the food system and visits to agroecological farms. Similar initiatives exist in cities around the globe and flourished during the Covid pandemic. Community kitchens like the Cuisines de Quartier cannot be reduced to mere physical infrastructure but function as an empowering device and work effectively as a piece of social infrastructure with the potential to reconfigure the labours and relations of social reproduction out of charity models.

Beyond charity models and food waste

“Surplus” food discarded by the mainstream food supply chain is abundant, and there are often financial incentives to access it (i.e. it is cheap, or free). However, this is often food that is conventionally grown (using agrochemicals and pesticides), shipped from the other side of the planet, and unfairly paid to farmers and farmworkers, who struggle to obtain dignified livelihoods. Charity-based food projects often rely on donations to distribute the food to people in need, without challenging the injustices in the food systems that affect farmers and consumers.

One of the key challenges for community kitchens is to move away from this food (and these allocation models), and accessing agroecological food, which is healthy for people and for the planet, and grown and marketed with justice. This is particularly difficult when the aim is to source food locally (which is more expensive than imported food), when people most in need are on low incomes, and when culturally appropriate food can not be grown locally. The Granville Community Kitchen in London is an inspiring organisation in the North-West London. While at present, Granville is not yet able to organise food aid without surplus food from the mainstream food supply chain, they have undertaken several actions to provide as much as possible local, healthy and socially just food. One of the core values of the organisation is also to provide for culturally diverse dietary needs. For example, through a veg box scheme called ‘Good Food Box’ in a pay-what-you-can principle, they cater for a wide range of eaters, providing optional African and Carribean Heritage bags. By linking community supported agriculture (CSAs) models (producers-consumers alliances), with equity models (sliding scales of veg-box, to allowing the creation of an equity fund), and when necessary, by importing from agroecological producers cooperatives overseas, community kitchens can enable a much broader access to good food, that would otherwise only be available to middle classes.

Sharing among family members, friends, neighbours and colleagues

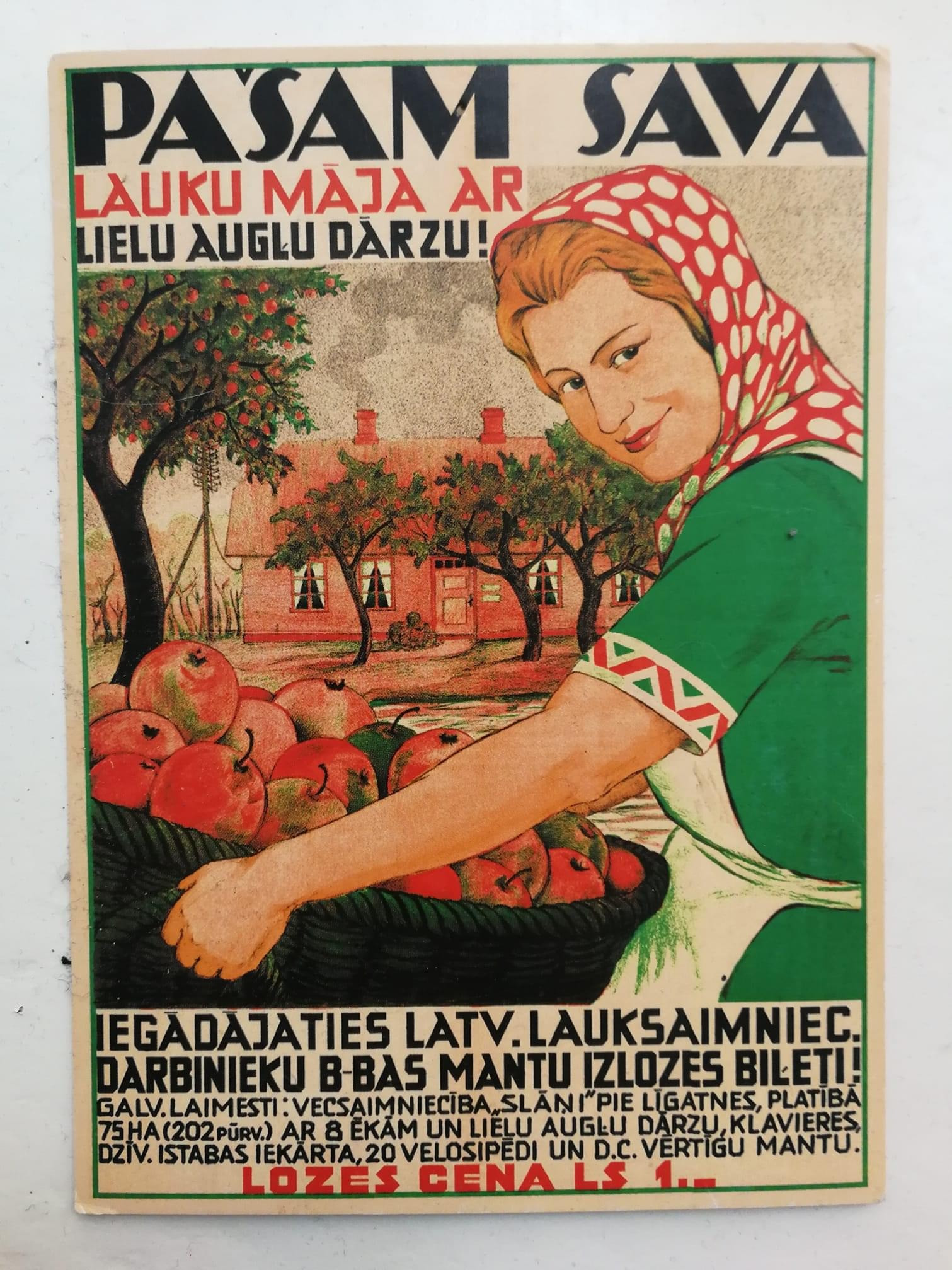

In amateur gardening and livestock farming, an occasional or seasonal overabundance of produce is inevitable. In the Latvian context, not unlike other post-socialist states, the free sharing of surplus is still a common practice and rooted in a long history of auto-production. Sharing is not limited to family members, but includes a wider network of colleagues, friends, and neighbours. This tradition partly stems out of a sense of solidarity and dates back to times of Soviet occupation when food and other resources were scarce, and family members of different generations had to actively support each other. While today, sharing is no longer a bare necessity, interviews carried out as part of the Urbanising in Place project show that people find joy in offering others self-grown food, and feel pride for their own accomplishment. And even those in need do not hesitate sharing the surplus of their self-grown produce.

These practices are often not considered within sustainable food planning initiatives. Individuals and communities involved in informal practices of food sharing are not campaigning around such practices. Local farmers engaged in direct selling initiatives tend to replace informal traditions of sharing. Can we imagine urban food policies in which self-growing and sharing practices would be celebrated and valorized?