Open spaces in the city are scarce and claimed by many agenda’s: biodiversity, water infiltration and buffer capacity and healthy spaces for recreation. And, evidently, residential pressure is the most common for these remaining open spaces. Paradoxically, we define housing quality to the proximity of open space. In other words, it is a snake biting its own tail. And while cities are preparing and willing to transform and adapt to become more climate resilient, also including food production, it is often the first one that gets lost in the process. How can we include logics of food production and climate adaptation in a radical and transformative way in urban renewal and even investment strategies?

The agro-developer approaches the task of urban transformation and renewal from the point of view of agriculture. As a parallel to 'transit oriented development', where housing densification projects are linked to transport nodes, a strategy popular for the last decades, we could imagine its productive counterpart. As such, the agro-developer redirects housing and other investments towards 'farming oriented development'.

Contested housing

The closer to the city, the harder the tension between urbanisation, agriculture and nature rages on. Every bit of open space is under threat, because of the many agenda's projected onto it, whether it is climate adaptation (e.g.flooding areas) or further new residential development to cater for the demographic growth, typical for an arrival city. How the city caters for this influx is problematic on two fronts. On the one hand, there is an acute shortage of qualitative green space in Brussels. In many Brussels neighbourhoods — especially the most precarious — residents do not have access to green space within a ten-minute walk from their homes. On the other hand, affordability of qualitative housing is also an enormous challenge. A large part of the building stock is in need of renovation, especially since the energy ambitions. In the Brussels Region, with 66.6% of total direct GHG (green house gases) emissions in 2013, buildings are the largest sources of direct GHG emissions. In a way, you could say that the housing stock is as much facing pressure for transformation as farmland, and its future is as contested. It poses the question: what would it mean to connect the needed transformations of urbanisation, agriculture and nature?

Accessibility of green space expressed in a 10-minute walk

Contested Housing, meaning housing under pressure because of climate risks such as flooding or erosion, renovation needs, lack of accessibility, etc.

Atelier Groot Eiland is a social economy organisation committed to giving people a better chance on the labour market and has been active in Molenbeek, Brussels for over 40 years. The non-profit offers work experience, pre-training, employment support and job support. The organisation has grown to become a collection of mini-companies, offering training in a wide range of skills: the Bel Mundo and RestoBEL restaurants, the Bel'O sandwich shop, the Klimop carpentry shop, the Bel Akker urban vegetable gardens and pick-your-own farms, The Food Hub organic shop, the creative workshop and the bakery of ArtiZan, each have their own employees and customers, and thus respond to the needs of different neighbourhoods in Brussels. The organisation is particularly investing in connecting to the surrounding neighbourhood and actively strengthening a local Molenbeek identity – leading to a lovely mix of French and Dutch in their social media. More recently, Atelier Groot-Eiland has started a 1.5 hectare self-picking CSA project in the peri-urban area and is more and more approached by urban actors and local authorities to actively participate in urban redevelopments, acting as a socially driven and sustainable placemaker.

Food Oriented Development

It is striking to see that actors such as Atelier Groot-Eiland are more and more asked to act as a socially-driven placemaker, while this is actually quite far from their core mission. We observe other first attempts of connecting housing and agriculture in a common development model.

Another inspiring example from Brussels can be found at Le Logis-Floréal in Watermael-Boitsfort. There used to be an orchard in the centre of the garden district. It had been neglected over the years. But a few years ago, a CSA farm, with a self-picking garden and allotments, emerged on the site. The piece of open space was soon earmarked for a new residential development. The neighbourhood successfully opposed the building plans. An action committee mapped out vacant buildings in the neighbourhood and presented their findings to the Brussels Government Architect. The latter sought alternative sites for the houses together with the neighbourhood. The survival of the farm was safeguarded.

Another example is Werve Hoef in Wijnegem, a social housing project in which the public space is designed as one large CSA farm, managed by De Landgenoten. De Landgenoten is a cooperative and trust that buys farmland for landless organic farmers. In that way, they are able to support new farmers that have difficulty accessing land while guaranteeing the organic way of farming on that land. In this case, De Landgenoten manages the land and employs organic farmers. The project proves that social housing can go hand in hand with a socially inspired agricultural model.

The examples demonstrate that agriculture can also have a community-building function – just like a school, a community centre, a sports club, shops or catering establishments. We see all these as essential to a good quality of life, essential to the proper functioning of a neighbourhood. Agriculture is not on the list.

In the jargon of urban planners, people sometimes speak of 'Transit Oriented Development'. That means concentrating urban development around mobility hubs. You could also apply that logic to agriculture. Could we work out a 'Food Oriented Development' , a strategy that affords agriculture and food production a central place in the city?

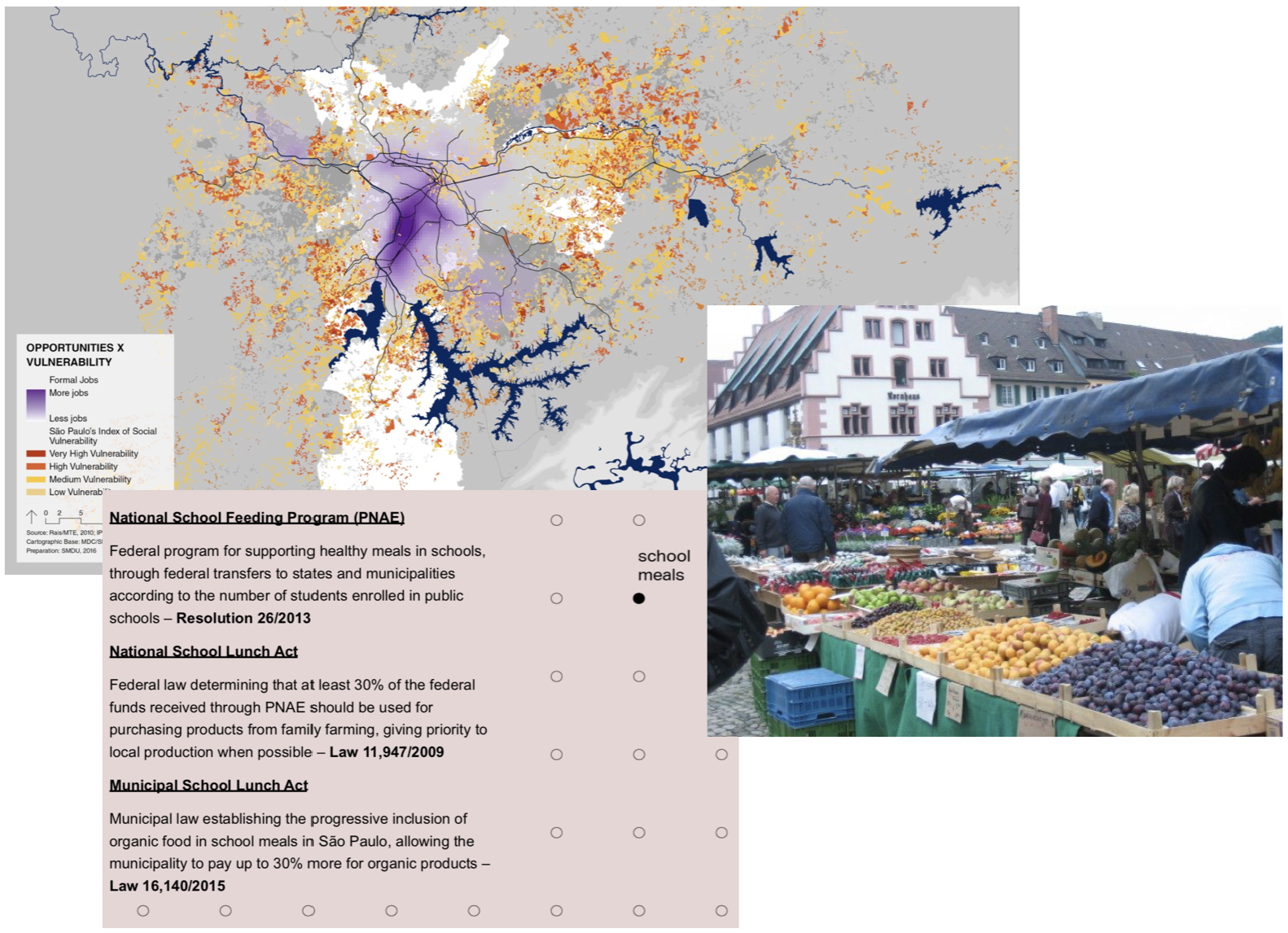

One last inspiring is in São Paulo in Argentina, because it is about planning urban food without spatially planning it: it is more about taking structural actions on a systemic level, thus influencing the processes of urban transformation. Following a demographic displacement of the rural hinterland towards the city, which created massive unemployment and food shortages in the city centre, the local authority of São Paulo has decided to source 30% of its public meals (schools, hospitals, etc.) or 6.3 million meals per day with family farming (almost totalling the amount of Flemish people in Belgium). This was an initiative that has been legally secured as a public procurement requirement and set up by the goverment. The sudden huge demand for local food has influenced the market to organise itself and has re-activated farming in the peri-urban areas considerably.

Images from the São Paulo project