How can we move beyond this conversation stopper?

Fighting the struggle of housing and growing rights together

The Land Justice Network is a coalition of grassroots actors in the UK that have started up a series of remarkable initiatives around a people-driven land reform, placing principles of the equitable sharing of land at the core. One of the notable things about the coalition of partners behind the Land Justice Network is that it not only includes groups mobilising around access to land for growers and land workers but also groups that are fighting for housing rights, and more generally groups focussing on decolonisation. The People's Land Policy is a shared mission statement referring to the People's Food Policy by the Land Workers Alliance. The strength of the coalition is the clear desire to fight the various struggles over land together. Where current capital-driven processes of urbanisation play various forms of land use against each other, using bidding rent and market competition as the determining factor in allocating land, the People’s Land Policy inspires us to imagine an agroecological urbanism where the use value of soils becomes a leading factor, and where the reproduction both of the right to live and to cultivate are secured together rather than in competition.

Proximity matters and comes at a price

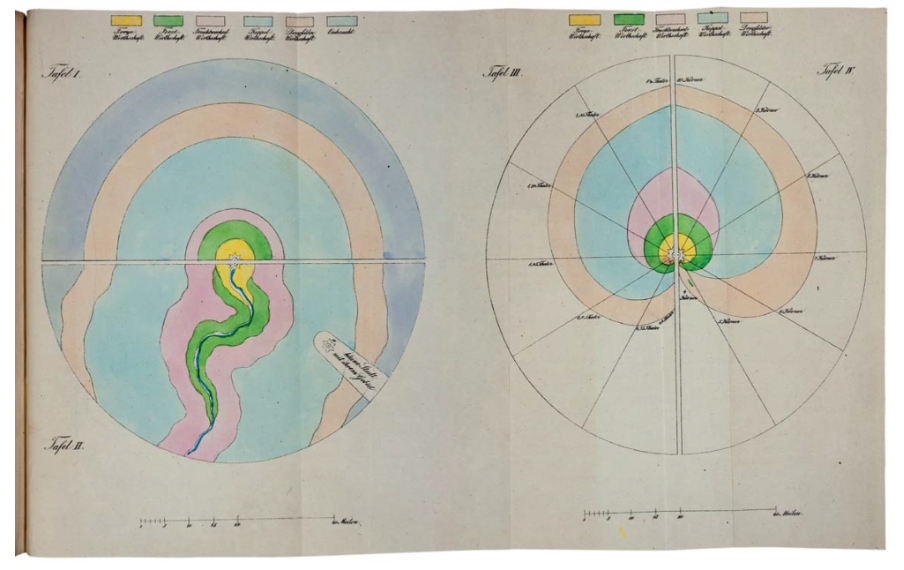

Thünen, Johann Heinrich von, Der isolierte Staat in Beziehung auf Landwirtschaft und Nationalökonomie (Rostock, 1842)

In the early nineteenth century, a German economist, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, studied how agricultural production organises around an isolated city. His model "the Isolated State" gives a mathematical explanation for the typical differentiation in land use he observed around German provincial cities based on the economical trade off between the prices within an urban consumer market, cost of land, the cost of transport and the cost of labour. He describes four rings around the city, with the first ring supplying dairy, fruit and vegetables (because perishable), the second ring timber production (because heavy), the third ring bulk crops such as grain (better storable and transportable), the fourth ring livestock farming (self-transporting), and beyond wilderness. Much has changed since Von Thünen's time. Nevertheless horticultural activities remain dominant in a peri-urban environment until today, not so much because there are no alternatives to getting fresh vegetables into the city, but because horticultural activities generate high yields in a small area, and are thus more able than arable farming and livestock farming to cope with high real estate prices and pressure on peri-urban land. From a 21st century perspective the “Isolated State” reveals the logics of substitution at play in a contemporary urban land market, where it has become possible to trade agricultural land use for urban activities that correspond with a higher land value. One of the main causes for this structural substitution is the relatively low cost of transport of (even fresh) food over long distances and the replacement of local land and labour for the extraction of resources and the exploitation of labour elsewhere. While these logics of substitution seem to make room for housing and amenities, and enable urban development, they are at the heart of a way of urbanisation that seems to accept the steady loss of land and farmers which are essential to the organisation of an equitable and sustainable urban society.Can we imagine the strategies and type of projects to revert these logics of substitution?

Cooking together is a good start

The network of the Cuisines de Quartier started in Brussels in 2019, originating from several previous action-research projects looking into the accessibility of healthy and organic food. Of course, the price came up as an issue in these trajectories, but also the lack of decent kitchen infrastructure and time for cooking, and cultural and dietary differences were identified as obstacles. As such, the non-profit organisation supports mostly self-organised community groups to frequently cook together and connects them to kitchens, for example the one of a local community centre or school. Although inspired by the Cuisines Collectives in Quebec, the network of Cuisines de Quartier (neighbourhood kitchens) specifically does not only target precarious groups, but strives to be a movement with a big diversity of groups that can learn from each other. Several activities are set in place within the network to link to agroecological initiatives, such as pedagogical activities and games on needs, cultural habits and demands, understanding of additives and the food system and visits to agroecological farms. Similar initiatives exist in cities around the globe and flourished during the Covid pandemic. Community kitchens like the Cuisines de Quartier cannot be reduced to mere physical infrastructure but function as an empowering device and work effectively as a piece of social infrastructure with the potential to reconfigure the labours and relations of social reproduction out of charity models.

No agroecology without decolonisation

“It is that big ecology of care, I would also say it’s a queering ecology. And by queer I mean about disrupting and dismantling white European straight male frameworks and contexts. And so we are decolonial in practice, and we go beyond just being feminists, as I said we’re queer and spiritual because a lot of us are coming with spiritual practices and beliefs. And so for us that solidarity is collective in arriving at collective understanding and values and each others offering something.”

Deirdre Woods, Granville Community Kitchen

The foundations of the modern agri-food system are in European colonial projects that have violently tried to destroy indigenous land, land practices and foodways. And so disrupting and dismantling white-supremacist, patriarchal and euro-centric knowledge structures is integral to forming agroecological economies and localised distribution networks. In terms of developing urban agroecologies, this includes the binaries of human vs. nature, urban vs. rural that underlie urban hegemonies and limit the ways of imagining and developing cities as agroecological places. Practices that support the collapsing of historical binaries, through processes of political contextualisation of urban life, re-humanisation, and positive identity formation, are critical to developing urban agroecologies.