How can we move beyond this conversation stopper?

Growing space as planning requirements

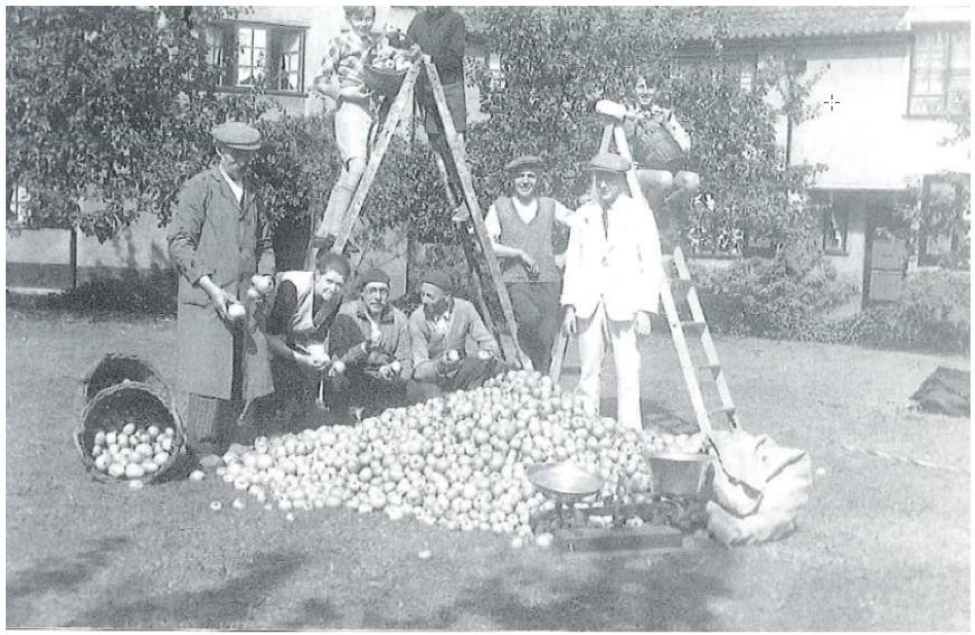

Cueillette des Pommes à la cité‐jardin – Le Logis-Floréal À Watermael-Boitsfort, 1940

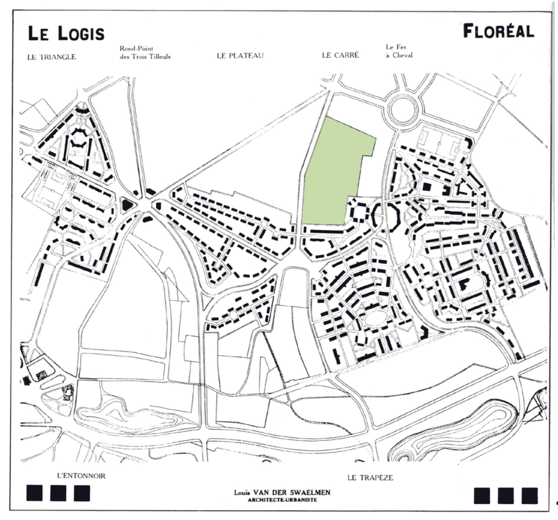

The Ferme du Chant des Cailles is a collective urban agricultural project initiated by farmers together with local citizens in a residential neighbourhood in Watermael-Boisfort, in the south-east of Brussels. The land on which the farm was established lies in the heart of the Logis Floréal, a garden suburb developed in the 1920’s designed by Louis Vanderswaelmen. The land was reserved in the original plan for a farm that was never built, but the settlement included individual productive gardens, productive fruit trees in the public domain and an orchard. The pressing need for new social housing in Brussels led the authorities to consider the land historically reserved as a productive space for the construction of 250 additional housing units, especially since the social housing company was owner of the land. However, the mobilisation of local citizens put the process of the development project on hold. The coalition of citizens even mapped vacancies in the neighbourhood, questioning the need for new development. What started with the idea of repurposing an abandoned field developed into a process of reappropriation of a historical urban pattern, relinking housing and food production, underlining the need for new planning tools and processes that consider community-build food production as equally valuable on the urban agenda as housing, schools or playgrounds.

Historical plan of Louis Vanderswaelmen with the historical productive land that today hosts the Fermes du Chants des Cailles highlighted

Building on the effective use of zoning as a counterspeculative measure

Spanish cities have been able to protect farmland on the peri-urban fringe through effective land use instruments and the establishment of so-called agricultural parks. The measures have been reasonably successful in stopping the destruction of agricultural soils (Miralles I Garcia 2015, 2020) but show mixed results when it comes to delivering a transition towards agroecological ways of farming. Many of these agricultural parks are situated within naturally sensitive areas. This provides clear opportunities to link nature development and biodiversity goals to the establishment of conditions in which only certain farming models can thrive. Agroecology can be a gamechanger in such a context, as it is a farming model that can accelerate the evolution towards nature inclusive forms of farming and move beyond the conflict between environmental goals and agricultural development. Zoning measures aimed at protecting farmland may be supplemented with legal measures to protect high valued soils, as is the case in the Parque Agrario de Fuenlabrada, near Madrid (Yacamán Ochoa, Mata Olmo, 2017). The categorization of soils goes hand in hand with the installation of farming models that start from principles of soil care and the ecological reproduction of soil fertility.

When agroecology reorganises your municipality

“Agroecology demands the complete reorganisation of municipalities. People from social economy, food production, the environment, health and planning, they all have to work as one multidisciplinary team.” according to Raul Terrile, one of the driving forces behind the Urban Agriculture Programme of Rosario. “ Key member of the agroecological movement joined the ranks of the municipal administration and reached out to their new colleagues across different departments. It set off a wave of collaboration and capacity building across the urban administration that ensures the rootedness of healthy food in the capillaries of urban policies and investments.

Dormant public land was made available; the former plant nursery for urban park management became an agroecological reference centre; parks were turned into garden parks, urban waste streams resourced for composting, buffer strips between roads rendered productive; the housing department started to stimulate growing on terraces and balconies; hospitals provided land for medicinal gardens; prisons set up demonstration gardens and many schools today cultivate their own educational garden. Looking at the list of what has been set up in the last 20 years, one begins to see the cross-over between urban and agroecological infrastructure. This summary can be read as a wish list for a future urban centre for agroecology. It is the result, however, of a persistent and consequent strategy to wield agroecology as an integrating and transversal urban strategy and bundle public investments accordingly.

The Rosario Agroecological Centre (CAR) is a public space that was implemented in 2017 within the framework of the Urban Agriculture Program of the Social Economy Secretariat of the Municipality of Rosario, to seek innovative responses to the demands of new actors interested in urban agriculture. The centre played an important role in valorizing and giving visibility to the knowledge and techniques built jointly in the territory during the last 30 years. The CAR works with research institutes, educational institutions, orchard organizations and non-governmental organizations, social movements and is associated with the Secretary of Extension of the National University of Rosario, the Polytechnic Institute, the Ministries of Production and of Health of the province and the Secretaries of Health, Environment and Production among other municipal dependencies; the Municipal Employees Association (AMTRAM), the Institute of Physics Rosario (CONICET – National University of Rosario), the National Institute of Agricultural Technology INTA and the Association for Biological-Dynamic Agriculture of Argentina.

No agroecology without decolonisation

“It is that big ecology of care, I would also say it’s a queering ecology. And by queer I mean about disrupting and dismantling white European straight male frameworks and contexts. And so we are decolonial in practice, and we go beyond just being feminists, as I said we’re queer and spiritual because a lot of us are coming with spiritual practices and beliefs. And so for us that solidarity is collective in arriving at collective understanding and values and each others offering something.”

Deirdre Woods, Granville Community Kitchen

The foundations of the modern agri-food system are in European colonial projects that have violently tried to destroy indigenous land, land practices and foodways. And so disrupting and dismantling white-supremacist, patriarchal and euro-centric knowledge structures is integral to forming agroecological economies and localised distribution networks. In terms of developing urban agroecologies, this includes the binaries of human vs. nature, urban vs. rural that underlie urban hegemonies and limit the ways of imagining and developing cities as agroecological places. Practices that support the collapsing of historical binaries, through processes of political contextualisation of urban life, re-humanisation, and positive identity formation, are critical to developing urban agroecologies.

Community Kitchens as Places of Solidarity

“I will now speak of the immense impetus I believe co-operative housekeeping would give to farming, and the revolution it would bring to it. [...] It will be the first aim of the co-operative housekeepers then, [...] to secure for each society a landed interest of its own.”

C.F. Pierce, Cooperative Housekeeping, 1870

The historical movement for co-operative housekeeping brings the burgeoning reflection of cooperative enterprise of the workers movement into the sphere of domestic work. Pierce's revolution begins in the kitchen and in the de- and reconstruction of the many social, political and economic relations wrapped up in it. Taking control of the kitchen is taking control of the many relations of dependency reproduced in everyday life. Today this translates directly into the decolonial struggle and unexpected forms of solidarity that come out of community kitchens.

A transformative community kitchen based on the principles of agroecology can play a pivotal role in the radical restructuring of the entire food system, including both relations with producers (near and afar) and urban consumers. By accessing urban and peri-urban land or liaising with peri-urban farmers they can contribute to develop a territorial food system, mindful of farmers’ livelihoods. By making the food broadly accessible, it addresses injustice in the availability of healthy food for all. By cooking and eating together, it can break with patriarchal and individualised approaches to food. By also sourcing food overseas from agroecological farmers, it can make available culturally appropriate food to a wider group of people. By organising forms of political engagement and knowledge sharing within the territory, alongside convivial initiatives, the kitchen can encourage the broader resourcefulness and solidarity, vis-a-vis the neoliberal city.